Stephen Whitehead

Effective use of community sentences relies on the relationship between courts and probation organisation. If the courts do not understand, or do not trust, probation organisations, then they will be less likely to place offenders in their supervision, potentially leading to overuse of custody.

Our recent report Renewing Trust explores the state of that relationship, and looks at how it can be improved. Here are a few of our key findings:

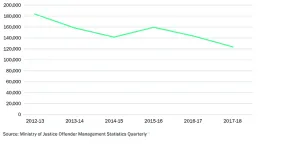

1. The number of pre-sentence reports has fallen by a third in five years

The number of new Pre-Sentence Reports produced, 2012/13 to 2017/18

Pre-sentence reports (PSRs) are reports written by probation officers to inform judges’ and magistrates’ sentencing decisions. They provide them with an assessment of the risk posed by an offender and the needs which are driving their offending, and a recommendation of an appropriate sentence. Sentencers are usually expected to request a PSR before passing a community or custodial sentence. However, between 2012/13 and 2017/18 the number of PSRs passed each year fell from 185,000 to 124,000. The causes of this fall are highly contested.

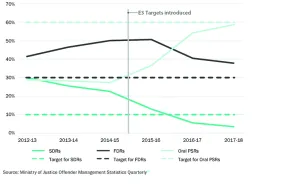

2. In just three years, the proportion of pre-sentence reports delivered orally has doubled, while the proportion given full “standard delivery reports” has fallen by 85%

Pre-Sentence Reports issued by type, 2012-13 to 2017-18

There are three types of PSRs:

- Oral fast delivery reports (FDRs) which are delivered on the day in court,

- Written FDRs, which are short reports, usually prepared during an adjournment

- Standard delivery reports (SDRs), the most comprehensive form of report which is always delivered after an adjournment

The National Probation Service’s (NPS’s) E3 Operation Model, which was introduced alongside the 2015 Transforming Rehabilitation (TR) reforms set demanding targets for changing the mix of different PSR types. Since it was introduced, the number of oral reports has doubled and the number of SDRs has fallen by 85% taking it well below the target.

Our research suggests that oral reports are adequate for most cases, though care needs to be taken to ensure they allow offenders to access treatment if required. However, there is concern that some complex cases which should have SDRs are getting written FDRs, leading to less robust recommendations being made.

3. Since the Transforming Rehabilitation reforms, judges, magistrates and probation staff in many courts, don’t know enough about how probation is supporting offenders in the community

The TR reforms created a split between the NPS which is responsible for providing pre-sentence advice to offenders and 21 privately-run Community Rehabiliation Companies which manage the majority of community sentences. Our research has found that, due to a lack of communication between the NPS and CRCs, judges, magistrates and NPS court staff in some areas do not have enough information about the content of CRC-managed community sentences. They feel unsure of the range of support services available or key details of that support such as eligibility, or waiting times.

4. The rehabilitation activity requirement makes community sentences more opaque to judges and magistrates

The rehabilitation activity requirement (RAR), was introduced as part of the TR reforms to act as a generic requirement which could cover a range of rehabilitative interventions. When a court includes a RAR in a sentence they only specify the maximum number of days which can be included – the precise way in which those days are to be used is determined at a later date by the probation officer responsible for managing the offender. While this offers valuable flexibility, it has also reduced the capacity of sentencers to anticipate what will be offered to offenders if they impose a community sentence. In particular “days” are a problematic measure of the extent of support to be offered: one “day” can mean anything from a 15-minute interview to an eight hour training course.

5. Judges and magistrates still have few routes to follow the progress of offenders after they place them on community sentences.

It has long been the case that, once sentencers pass a community sentence, they usually have no way of following the progress of the offender. As one magistrate memorably put it, “it’s like sending people out into the wilderness”. This deprives them of an important feedback tool which can support their learning around effective sentencing, as well as creating as misleading picture since they will only come into contact with sentenced offenders who breach or reoffend. In our research many magistrates and probation officers were enthusiastic about the idea of rolling out “problem-solving courts” which allow sentencers to have ongoing oversight of offenders’ progress on community orders in complex cases.

Stephen Whitehead is the head of Evidence and Data at the Centre for Justice Innovation. He leads our work on Community Sentences.