We spoke to Trina Robson, director of Love Barrow Families, a Community Interest Company based in Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria.

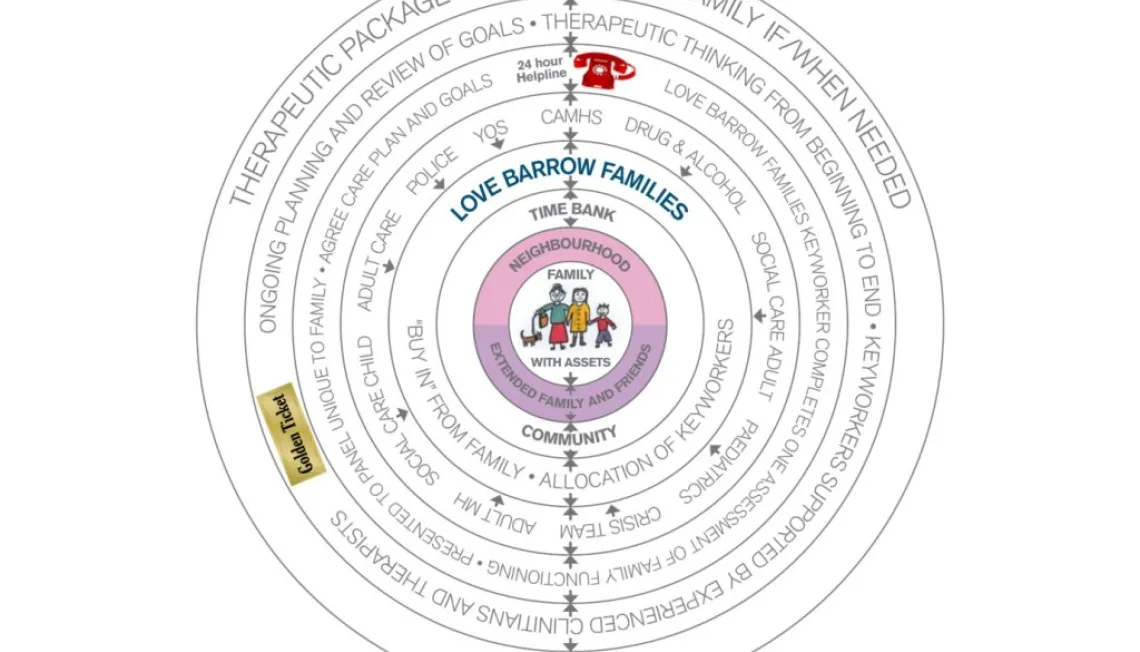

Founded in 2013 with funding from the Local Authority and NHS Trust, Love Barrow Families (LBF) is an integrated family service, combining children’s and adults’ mental health and social care. It works with families whose children are on a Child in Need or Child Protection Plan, looked after, or subject to care proceedings. By offering these families a single integrated service, LBF can get to grips with the underlying problems and engage parents by having the capacity to address all their needs.

LBF seeks to build the community's strength as a whole so that children can live happily with their families rather than entering the care system.

The Problem

Barrow-in-Furness is a small community which is amongst the 10% most economically deprived districts in England. Trina describes how in 2013, children’s services in Cumbria had been assessed as ‘inadequate’ for years, creating an environment in which it was impossible for the Local Authority to innovate. Consistent budget cuts meant that services were increasingly tightening referral criteria and limiting their parameters – encouraging a "refer on" mentality where every service was desperate to get cases off their books.

Trina was employed at the time by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS), and saw every day how the artificial split between mental health and social care, as well as adult and children’s services, made it impossible for social work to take a whole family approach which could properly address complex needs. As a result, the same families came to the attention of children’s and adults’ services time and time again, causing practitioners and service users alike a sense of exhaustion and malaise.

Building from the ground up

Trina knew that creating real change could only happen in collaboration with local families. With support from the New Economics Foundation, she and her colleague designed a programme of co-production which sought to underline the reciprocal relationship between service user and practitioner, asking each what they needed a family service to be. The proposals from parents and practitioners led to the creation of an integrated service, which worked from compassion and respect, while backing professionals to hold risk without fear of blame or repercussions.

Initially, the service was made up of a co-located multidisciplinary team of seconded public sector staff, including an adult psychiatrist, occupational therapist, family support workers and a lead social worker. Working from a room in a local primary school, LBF delivered what Trina describes as “everything” to twenty families; services ranging from statutory social work to practical advocacy and foodbank vouchers. At point of entry, each family is matched with a key worker who is the single point of contact for the service and who fields relationships with other agencies. Families also undergo a single comprehensive assessment.

Other elements of the service are designed to build the quality of life in the community as a whole. The LBF Time Bank allows parents using the service to contribute their specific talents to a central “bank”, in order to access other people’s resources in return. For example, one parent might deliver a cooking class, and in return receive help from a participant to decorate their home. The Time Bank underlines how LBF approach is strength-based and communal, investing in reciprocal social networks as the key preventative measure.

Seeking to understand ‘the details of people’s lives’

The assessments and psychological approach of the service has been very influenced by the American Psychologist Dr Pat Crittenden and her Dynamic Maturational Model, which broadens attachment theory to include family functioning and community contexts. Trina describes it as a tool which helps “us to understand the details of people’s lives” and it is at the heart of the radical relational understanding which drives the service.

Evidencing Success

The 2017 independent evaluation of LBF, undertaken by Dr. Sharon Vincent at Northumbria University, shows the project achieved a number of very positive outcomes. Vincent emphasises that ‘it is particularly notable that they have achieved these outcomes within a context of reduced and uncertain funding and with limited staff and this can be attributed to their innovative way of working as well as the commitment of their staff team.’

Headline findings are a reduced number of children going into or returning to care, significant reductions in the number of children on child protection and child in need plans, and improved mental and physical health experienced by family members. Significantly, the evaluation also evidenced families’ expressing increased levels of trust in services.

This sense of increased trust is echoed by professionals across Barrow who expressed how LBF has changed the area as a whole, with a local Police officer stating: ‘For the families the police has involvement with, it’s reduced police contact. It’s broken down barriers between the police and the families and the children in those families and it’s created a safer environment for the families. The families now feel they have a voice.”

Many professionals believed that LBF has indicated the need for services to use the principles of co-production, rather than allowing agencies to work in silos: ‘We need to hold a mirror up to the way we deliver services they are currently built around the needs of teams rather than looking outwards from families’.

The Financial Impact

In social care costs alone there were total savings of £68,350 for the LBF group compared to increases of £43,948 for the comparison group.

It is also likely there are further avoided costs that result from investing in the model, in terms of reducing the amount of children entering or remaining in care, and associated savings across public services.

Love Barrow Today

Since 2018, the service has shifted from being a seconded team from the public sector to a Community Interest Company. This means that LBF no longer deliver the statutory social work component of the service, which has reverted to the Local Authority. Families also access the service through an open door policy. With these changes, and significant new projects on the horizon, it will be exciting to see how the service grows.

If you would like to know more about Love Barrow Families or read their evaluation, check out their comprehensive website. You can also reach Trina on katrina@lovebarrowfamilies.co.uk.

This case-study was written by Albinia Stanley in 2019